Uttam Kumar: Stardust Eternal

- Jul 26, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 3, 2025

A charismatic cinema legend in his lifetime in Bengal, Uttam Kumar’s unfading brilliance continues to cast a magical spell across all generations -- his immortal legacy endures. A tribute to the Mahanayak on his 45th anniversary.

By Tathagata Chatterjee

Uttam Kumar (1926-1980) was not merely a star but a celestial force illuminating the Bengali film industry—affectionately dubbed Tollywood—from the early 1950s to the late 1970s, with an unmatched blend of charisma and craft. Born as Arun Kumar Chattopadhyay in Calcutta, he was both an intimate idol, cherished in the hearts of millions, and a towering cultural icon, commanding fandom, reverence, and unwavering loyalty.

A private man, he shunned the spotlight off-screen, guarding his mystique with calculated reticence, granting few interviews and shying away from public oratory. His films speak for his craft.

Uttam Kumar stands as a rare luminary, uniquely entwined with the revered Ray-Sen-Ghatak triumvirate (Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak) of Bengali cinema. However, in that rarified lay of the land, his journey ranged from the sublime to the ridiculous!

In Rajkonya (Portrait of a Princess, 1965), scripted by Ritwik Ghatak, he navigates a lackluster tale of palace intrigue with his characteristic poise, lending depth to a muted narrative.

In Mrinal Sen’s debut film Raatbhore (The Dawn at the End of the Night, 1955), a soppy film which Sen disowned since, Uttam was part of an impressive cast, alongside Chhabi Biswas, Sabitri Chatterjee, Chhaya Debi, Sova Sen, Jahar Roy, Kali Banerjee, etc. The plot centered around a 14-year-old orphan, a restless village soul tormented and adrift, evading the suffocating grasp of a wealthy, childless Calcutta couple.

Probably the massive lineup of cast members created a problem for the young and inexperienced Sen. As a result, Sen lost all interest in the film even before it was made. He tried to give a negative angle to Uttam Kumar’s character by making him virtually a villain, but neither the audience nor the star himself was happy about it.

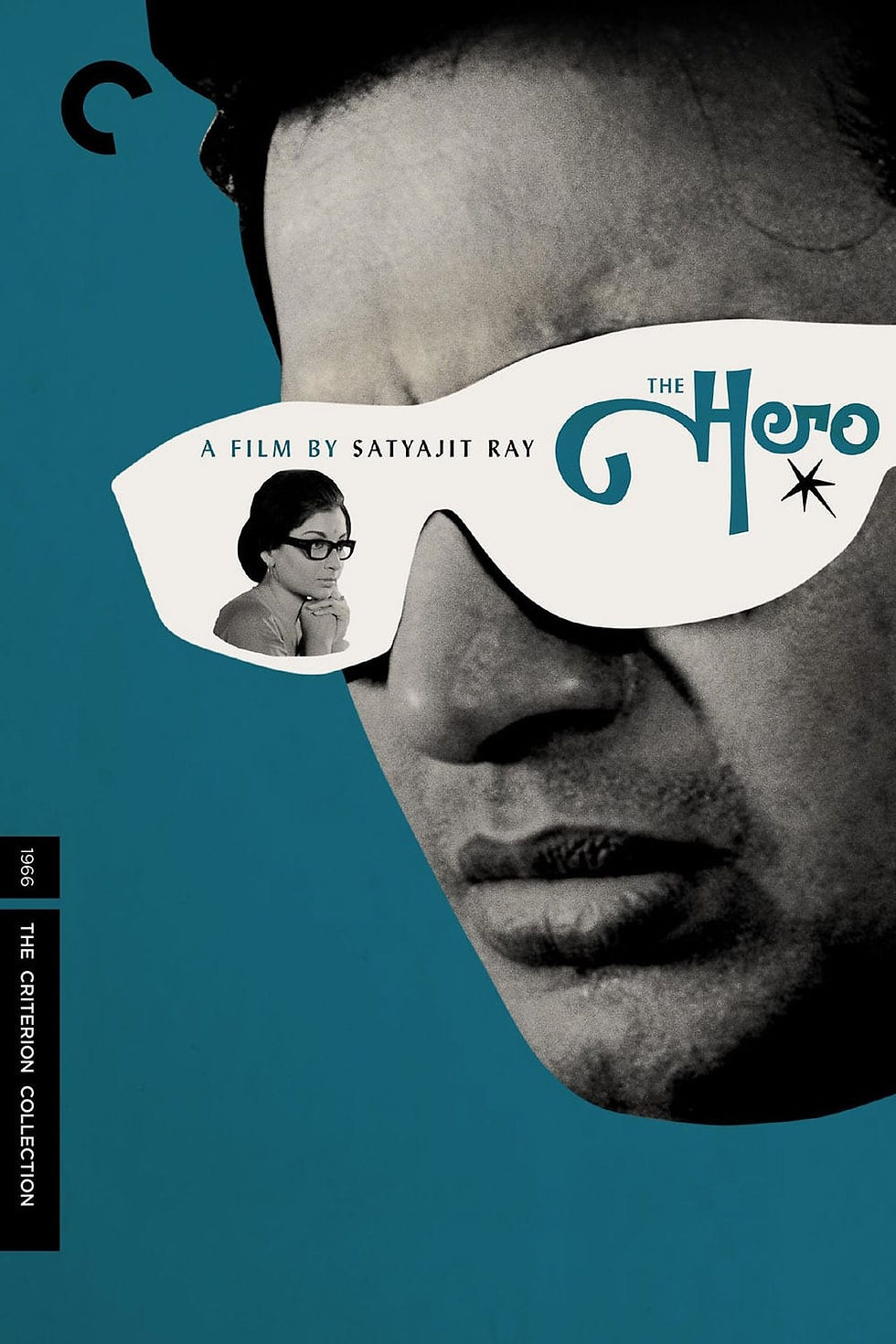

And, of course, a decade later, in Satyajit Ray’s Nayak (1966), his tour de force as a conflicted matinee idol cements his legend, baring the soul of stardom with unparalleled finesse.

Speaking of which, famously, in 1966, after accompanying Ray’s Nayak to the Berlin Film Festival, he sidestepped a London television interview, perhaps wary of his faltering English beside polished Western counterparts.

Whispers persist—though unverified—that Elizabeth Taylor, captivated by Nayak’s screening in London, expressed a desire to collaborate with Kumar, struck by his magnetic versatility.

Unbound by the studio system, he single-handedly defined Tollywood’s star era, appearing in over 200 films, nearly half of which remain etched in Bengal’s cultural memory as timeless treasures. His performances, marked by an effortless fusion of vulnerability and gravitas, continue to resonate, a testament to a legacy that transcends time.

In 2024, Srijit Mukherji’s Oti Uttam (Too Good) resurrected Uttam Kumar after 37 years.

The plotline was simple: Krishnendu (Anindya Sengupta), a devoted scholar immersed in a PhD on Uttam Kumar, pines for the aloof Sohini (Roshni Bhattacharya), his unrequited love. Desperate, he enlists his friend Gourab Chatterjee—Uttam Kumar’s real-life grandson, playing himself—to conjure the spirit of the legendary matinee idol. Who better than Bengal’s ultimate ‘love guru’, whose silver-screen charisma enraptured millions, to steer Krishnendu through the labyrinth of romance?

The film became a box-office triumph. It used VFX to weave snippets from 54 of his films into a modern narrative, with Kumar’s voice -- channeling conditions for his ‘return’ through his grandson—forcing ingenious narrative hacks to bridge archival discontinuities.

These constraints, born of limited resources, sparked Mukherji’s creative alchemy, tailoring dialogue to fit context and vice versa, though in scenes the mimicked voiceovers lack the original’s captivating aura.

This audacious tribute, both technological marvel and heartfelt homage, transforms archival poverty into a rich tapestry of memory, reaffirming Kumar’s timeless allure. To grasp the full measure of his artistry, one must turn to the performances that defined his cinematic immortality.

Here is my curated selection of Uttam Kumar’s 20 finest performances, presented in chronological order, a heartfelt homage on his 45th death anniversary (July 24, 2025). A nostalgic tribute to those cherished Bangla Doordarshan black-and-white evenings, spent enthralled, alongside my grandmother and aunts.

Note to self: This list evolves with each passing year, reshaped by the tides of my growing maturity and shifting emotions.

Harano Sur (The Lost Tune, 1957) – As an amnesiac haunted by fractured memories, Uttam weaves a tapestry of pathos and resilience, embodying a romantic soul lost yet yearning for redemption. Inspired by Random Harvest (1942) by Mervyn LeRoy, starring Ronald Coleman and Greer Garson. (Dir: Ajoy Kar).

Bicharak (The Judge, 1959) – As an erudite, ethical, atheistic judge confronting his shadowed past, his steely gravitas unveils a man wrestling with guilt and moral reckoning, having allegedly abetted his first wife’s death from apathy. Incidentally, Uttam learnt to play tennis for just one scene in this film, and later on occasionally played for real at Calcutta’s South Club. (Dir: Prabhat Mukherjee).

Soptopodi (The Seven Steps, 1961) – As an audacious medical student navigating life’s transformative crucible, he radiates youthful fervour tempered by poignant discoveries on the road to true love. Here, a couple of the climactic scenes from Othello were enacted by Uttam and the ethereal beauty, Suchitra Sen. The dubbing for the roles of the misunderstood Moor and Desdemona were done by two leading Indian Shakespearean thespians: Utpal Dutt and Jenniffer Kendall respectively. (Dir: Ajoy Kar).

Deya Neya (A Romantic Exchange, 1963) -- As a secretive singer sacrificing anonymity for a friend’s survival, his soulful restraint weaves altruism with the ache of self-exposure. (Dir: Sunil Banerjee).

Shesh Anko (The Final Act, 1963) – As a charmer in love with a much younger woman with a shadowy past, he may have killed his offending wife, laying himself open to an elaborate mousetrap. His searing intensity re-imagines the British crime drama Chase a Crooked Shadow (Dir: Haridas Bhattacharya).

Jotugriha (House of Wax, 1964) – As one-half of a fractured marriage collapsing into an inevitable divorce, his ‘disillusioned yet caring husband’ captures the quiet devastation of love’s erosion with searing nuance. (Dir: Tapan Sinha).

Thana Theke Aaschi (An Inspector Calls, 1965) – As a no-nonsense sub-inspector who slowly unmasks the venality of the typical Bengali bhadralok household with his methodical probing and piercing gaze, unearthing the circumstances that led to the death of a woman with chilling precision. Original Inspiration: Adapted from JB Priestley’s 1945 play, An Inspector Calls. (Dir: Hiren Nag).

Nayak (The Hero, 1966) -- As a matinee idol unmasking his vulnerabilities, Uttam delivers a tour de force, peeling back stardom’s sheen to lay bare his securities and choices. (Dir: Satyajit Ray).

Antony Firingee (Poet from Another Land,1967) – As a besotted Portuguese-Bengali poet, Hansman Antony, who is doomed by fate, Uttam’s soulful portrayal blends cultural fusion with tragic inevitability, etching a timeless elegy. (Dir: Sunil Banerjee).

Chowrongee (Chowringhee,1968) – As a lonely concierge-n-chief observing the vibrant microcosm of a luxury hotel, Kumar’s poised elegance reflects a city’s dreams and duplicities in a luminous urban tapestry; as he moves through the eclectic set of guests, inhabitants, and employees, ranging from shady businessmen, misfit musicians, tuxedoed managers to hawk-eyed lobbyists and secretive nightwalkers. In other words, the hotel is the city, and the city is the hotel. (Dir: Pinaki Mukherjee).

Nishi Padmo (The Night Flower, 1970) – As a solitary businessman veering for a ‘fallen woman’, his restrained empathy illuminates the delicate interplay of compassion and loneliness. As an inspiration to Hindi cinema’s first superstar Rajesh Khanna, who went on record stating he watched the film 18 times while preparing for Amar Prem – its Hindi version – and “with each viewing it dawned upon me that I cannot even hope to do a film that extracted the best from this extraordinary actor”. (Dir: Arabinda Mukherjee).

Chhadmabeshi (The Trickster, 1971) -- As a playful Botany professor disguised as a chauffeur to create an innocent web of identity theft, Uttam’s infectious wit laced with impeccable timing, delivers uproarious comedy, testing familial bonds with mischievous brilliance. (Dir: Agradoot).

Ekhane Pinjar (The Prisonhouse, 1971) – As a keen observer of a decaying moral landscape, his incisive performance as a celebrated author, lays bare the quiet despair of a decaying society adrift. (Dir: Yatrik).

Jodu Bongsho (The Parricide, 1974) – As an archetypal wretched loser who listens to the torments of people around him with empathy. In the climax, where he gets battered by false theft charges, Kumar’s raw vulnerability paints a harrowing portrait of society’s cruelty to the defenseless. Just watch how he acts with his eyes! (Dir: Partha Pratim Chowdhury).

Bikele Bhorer Phool (Love in Autumn, 1974) – As an ageing writer and scholar caught in love’s elusive dance, his wistful grace transforms a Billy Wilder-inspired 1957 film, Love in the Afternoon, into a meditation on unattainable desire. (Dir: Pijush Bose).

Amanush (The Savage, 1974 ) – As a zamindar’s heir reduced to a drunken wreck, his raw intensity channels the wreckage of fate with heartbreaking authenticity. The Hindi version too, with stellar performances by Utpal Dutt and Sharmila Tagore, was a big success. (Dir: Shakti Samanta).

Baghbandi Khela (The Hunting Game, 1975) – As a Machiavellian patriarch driven by ruthless ambition, his chilling intensity crafts an anti-hero whose power lust is both mesmerizing and monstrous. As someone ready to trick his own son without batting an eyelid. (Dir: Pijush Bose).

Nagar Darpane (In the Mirror of the City,1975) – As an advertising copywriter armed with an unforgiving sense of good and bad, finding himself at odds with everyone, as his familiar world crumbles and he submerges into despondency. (Dir: Yatrik).

Agnishwor (The Fire God, 1975) – As a principled doctor and covert revolutionary during the pre-Independence era, his steely resolve and quiet heroism paint a portrait of sacrifice in turbulent times. (Dir: Arabinda Mukherjee).

Dui Prithibi (Two Worlds, 1980) -- As an idealist brother bearing the weight of a debased era, Kumar’s dignified sacrifice elevates familial duty into a poignant, Christ-like odyssey. (Dir: Pijush Bose).

Uttam Kumar’s legacy endures, timeless, and untouched by the ravages of history.

Since his passing in 1980, when tens of thousands of various generations, especially women, joined his endless funeral procession in Calcutta, his cult has not merely persisted but flourished, drawing new generations through television reruns and digital streams, each viewer discovering anew his unparalleled allure. His films, replayed endlessly, command devoted audiences; his life fuels spirited addas across Bengal; his birth and death anniversaries remain cultural touchstones, often co-opted for political pageantry.

No wonder he is called Mahanayak.

Here comes my pet peeve. As Uttam Kumar’s star shines undimmed, the lamentable neglect of his cinematic legacy casts a shadow over his enduring cult. Unlike the meticulous preservation efforts seen globally for cinematic giants, no concerted initiative has safeguarded his classics, many of which languish in deteriorating prints, their visual poetry fading with time.

The absence of a dedicated archival movement in Bengal—akin to the Film Heritage Foundation’s tireless work to restore Indian cinema’s treasures—leaves his oeuvre vulnerable, depriving new generations of the pristine brilliance of his performances. An institution like the Film Heritage Foundation, with its expertise in restoration, is urgently needed to resurrect these films, ensuring that his transcendent artistry—still mourned and celebrated in addas and anniversaries—remains a vivid, accessible testament to his immortal legacy.

In the 1973 Bengali comedy film, Basanta Bilap (Sweet Nothings), a love-struck, ordinary-looking suitor, played with comic flair by Chinmoy Ray, shyly asks his beloved to call him “Uttam Kumar” -- just once -- sealing a moment of romantic whimsy and ultimate compliment.

In that fleeting scene lies a universal truth: within every romantic Bengali heart, Uttam Kumar’s name evokes a spark of eternal devotion and endless myths, a magical star whose light refuses to fade.

Acknowledgements:

Uttam Kumar – A Life in Cinema by Sayandeb Chowdhury (Bloomsbury, 2021).

Mrinal Sen, 60 Years in Search of Cinema by Dipankar Mukhopadhyay ( Harper Collins, 2009).

Tathagata Chatterjee is a Gurgaon-based marketing strategist who likes to say he’s “in a meeting” when he is re-watching a film for the twelfth time. An alumnus of Presidency College, Calcutta, and JNU, Delhi, he claims to be extremely busy, but somehow has an enviable amount of free time for popular culture, books, music, and making ambitious promises about “starting a book this year!”