‘Literature, fine arts and poetry thrive in turbulent times’

- Sep 29, 2025

- 11 min read

In Conversation: 'Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s most remarkable novels were written against the backdrop of the most turbulent times in Latin America. American literature flourished during the great depression. In Russia, the best literature came out during oppressive regimes.'

By Kumudini Pati

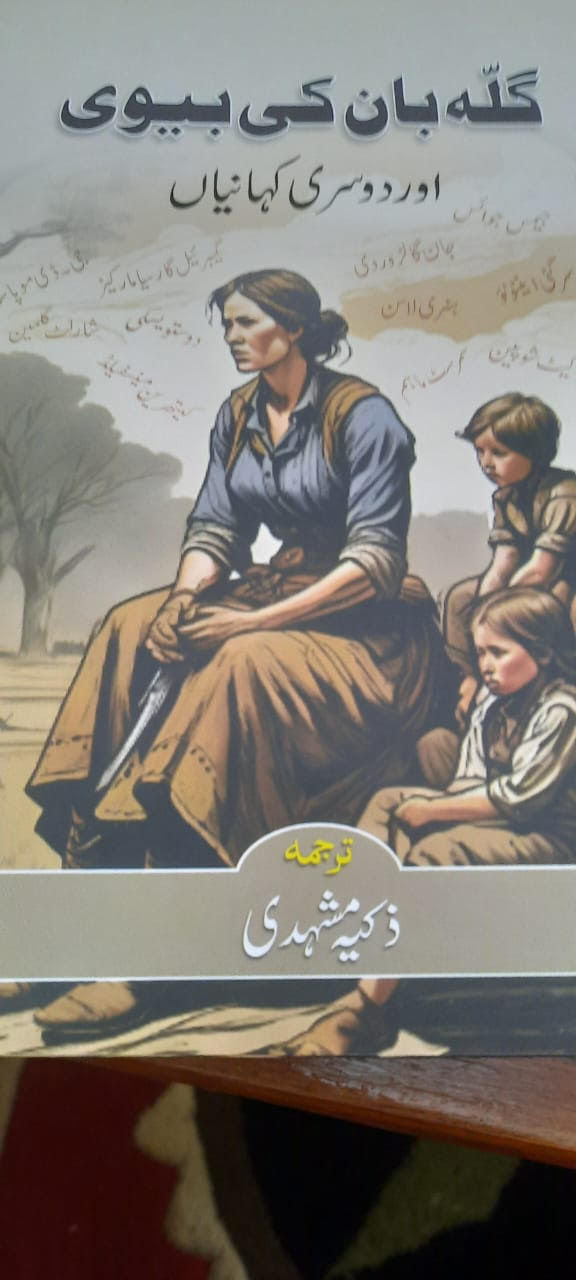

Zakia Mashhadi, based in Patna, Bihar, is an internationally acclaimed novelist, story writer and translator for Urdu, and has been a recipient of several awards like the Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Award from the Uttar Pradesh Urdu Academy, the Qatar-based Majlis-e-Firogh-e-Urdu Adab (MFUA) Award 2023 (International award for promotion of Urdu literature), the Iqbal Samman, the Ghalib Award for fiction (2016), Sahitya Academy Tarjuma Award (2018), Awards from Bihar University for the first three collections of short stories and many of the highest awards from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh Urdu Academies. She has to her credit collections of short stories, novels and translations of fiction, as well as academic books in Hindi, Urdu and English. In conversation with Left woman activist and freelance journalist, Kumudini Pati.

You are an internationally acclaimed author and have written so much. Which of your books would you rate as your best creation and why?

I don’t think I qualify to be called an internationally acclaimed author. In fact, it is embarrassing for me. My stories and translations have been well received by Urdu readers (a dwindling entity) of the subcontinent, that is all.

My books are largely collections of short stories. Of these, there are seven. I have also published two novels, though they are not my favourites. I think I need to improve a lot before I can be called an accomplished craftsperson of this genre. As for the short stories, I like all of them, barring a few early ones that I consider to be too simplistic or common-place.

I see that your writing has always related to social issues like patriarchy, Dalit oppression, discrimination on the basis of religion, family contradictions, etc. This was one reason I used to come to you to select stories for the women’s magazine I was editing during the 1980’s and early 90’s, Aadhi Zameen. I remember your story Chauthe Abba, which we published, was greatly appreciated. With inspiration from you we had started an Urdu supplement too. It stopped. I have heard that the readership of Urdu women’s magazines like Khatoon Mashriq, Pakeeza Anchal, Bano, Mashriqi Dulhan and Mashriqi Anchal has declined. The publication of Khawateen Ki Duniya was discontinued. What could be the reason? Is it because unlike the early women’s newspapers and magazines, like Tahzib-un-Niswan, Khatun, Ismat, the contemporary ones don’t challenge the status-quo?

You will surely agree with me, that Urdu readership has declined considerably. Most of the good literary magazines have shut shop. The reasons are many, and the issues involved will necessitate a detailed discussion. But it will suffice to say that women’s magazines, too, have suffered equally. Bano was one of the good ones with a liberal outlook, but it stopped (albeit due to a non-literary reason). Kahtoon-e-Mashriq is still being published, and so is Khwateen Ki Duniya. Maybe a couple more.

The magazines of today have nothing to do with challenging the status quo like the ones you have mentioned, i.e. Tahzeeb Ul Akhlaq, Asmat, etc. The ones mentioned-- the early ones-- started with the purpose of women’s education and instilling some peaceful ways to challenge patriarchy.

Now the scenario has changed, and with it the purpose of women’s magazines too. These magazines now contain short stories, abridged novels, articles on health and childcare, recipes, and religious queries. But there seems to be no specific aim or purpose. They do, of course, promote Urdu readership; we have to value them for that.

How is it you became sensitive to social issues? Was it your family background and the stories of Partition recounted by your parents and grandparents (you were only 3 years old then)? Or was it something else? Were you inspired by some authors of those times? Who were they?

I think, barring a few exceptions, all of us are sensitive to social issues, to varying degrees. These days, politics has become a hot topic. Much comes from our inherent nature and the rest from the impact of external factors. People discuss them, ponder over them, and try to solve them too. I live in the same society, facing the same issues, and write about what inspires or disturbs me the most. The power of the pen is the only thing that makes writers different from the common man.

As for partition, it is considered one of the ten biggest tragedies of the 20th century and one that changed the world. It still casts its shadow on social and personal spheres and continues to shape, to a large extent, the politics of today. The Kashmir issue is a monster that raises its ugly head now and then, routinely threatening peace in the subcontinent. Indian Muslims, though they chose to remain in India, bear the brunt of that decision, even today. So, one did not have to see the partition happening in 1947 to feel its impact. It is very much with us even today.

Of course, I did read some books of history and literature on the subject. In fact, I still read them. But I am not inspired by any of the authors who have made partition their subject. Partition is in my bones, one of the issues that makes me feel incredibly sad, and so it is natural that the subject, or rather its reference, shows up in some of my stories. It is one of the topics that I would like to explore further through my writings. It is a topic that (as a form of literary expression) will never go stale.

You are equally proficient in Urdu, English and Hindi. Would you like to name one author of each language who influenced and inspired you the most? Who were your favourite authors in these languages?

Like any educated Muslim from North India, I know Urdu, Hindi and English quite well, but I do not claim authority over any of them. Since I am very fond of reading, I have read from all these languages and translations from a few other European languages, too, and especially Russian. I have also read translations from regional languages of India that I am very fond of, especially Bangla, Tamil and Malayalam. I love good literature. I adore Anton Chekhov, Fyodor Dostoevsky, John Steinbeck, Thomas Hardy, Alice Munroe and many more. English is a vast ocean; I could pick only a few pearls.

Hindi and Urdu are comparatively less rich, but they too, can boast of many good writers, and I like many from this reservoir too. Qurratulain Hyder, Syed M. Ashraf, and Intezar Hussain from Urdu. Kamleshwar, Surendra Verma, Mridula Garg, and Giriraj Kishore come to mind from Hindi. I also like quite a few Bangla writers. I wish I had a hundred years to live, so I could read for a hundred years more.

Though people like you, Rakshanda Jalil and others, who run institutions for the promotion of the Urdu language, and are trying their best, the common people of India are being forced to believe that Urdu is the language of Muslims. How will it be possible to counter this opinion, that is fast gaining ground?

The belief that Urdu is a language of the Muslims (only) has taken root, which will not be easy to pull out, no matter how much it is refuted in meetings, discussions and articles. The idea has a long history, the origins of which can be traced back to the divide-and-rule policy of the British.

During partition, Muslims too had their share in widening the chasm. Now efforts should be directed towards bridging this gap and not widening it further. Joint literary programmes, translating works of noted authors from one language to the other, and conducting free Urdu classes can be some meaningful steps in this direction. All these are already being taken up by well-meaning people, but they are not enough. More effort is needed to show tangible results. In this age of science and technology, language and literature have taken a back seat; one must also be mindful of this reality.

In the turbulent times we are living in (wars against Palestine and Ukraine, Conflict in Kashmir and Manipur, subversion of democracy at home) can there be poetry, art and writing at all? Many people in the world are facing a kind of deep existential crisis. Some youngsters are driven to suicide, and many women are subject to unprecedented violence. Recently, we were even witness to the feminisation of war! Can art and literature thrive in such an atmosphere, and can they have some meaning when the air is filled with unrest and despondency?

Literature, fine arts and poetry have always been seen to thrive in turbulent times. They motivate dormant talent to give their best. American literature flourished during the great depression. In Russia, too, the best works of literature came out during oppressive regimes. Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s most remarkable novels were written against the backdrop of some of the most turbulent times seen in Latin America. Closer to home, we have seen some of the most remarkable works of poetry and fiction written when the country was facing the aftermath of partition. So, I am hopeful that the evils and chaos of the present day will not adversely affect literature. In fact, the voices of dissent and analytical approach will serve to bring out the best in us.

We are living in an age when the electronic media and more so, the social media, is occupying a space as large as never before. Youngsters are busy scrolling and watching endless number of reels. Their attention span has shrunk to a few seconds. In such a scenario, do you think Generation Z is going to enjoy books, stories, hour-long plays and poetry sessions? Don’t you feel it is a challenge for all authors and creative people to be able to catch the imagination of this generation of internet-savvy youngsters? What can one do as a literary person to rise to this challenge?

Yes, electronic and social media are a challenge to literature, but they also provide useful technical tools which help in propagating and dispensing it amongst the masses. Kindle, for example, is a cheaper and easier way of reading books that we desire. Literature from across the world is easily available at our fingertips through digital formats. Books are now safer. Hulegu or his ilk cannot burn libraries now.

Many literary portals are running on social media, giving an opportunity to lesser-acclaimed writers to present their skills to a vast and previously inaccessible audience. All the same, I personally notice that it has become difficult to publish newspapers and magazines in Urdu, which is a ghaate ka saud (a thankless, unprofitable pursuit).

Sadly, many publications have had to close shop as a result. Social media has stepped in and filled up this vacuum to a large extent by providing poets and authors with an alternative channel of engagement with their audience through these platforms.

One must also note that times do not remain the same. It is not social media as much as the lack of emphasis on professional education that has corroded literature. Still, where there is a will, there is a way. Those who have a genuine interest in literature will continue to study it and create it too. Let us remain positive.

What is the impact of popular culture on today’s youth? Is it killing value-based literature?

Popular culture has certainly brought many new trends to today’s youth. Their pursuit of quick, easy, and inexpensive entertainment, as well as the casual use of language that may not be considered appropriate, can at times distance them from value-based literature. Yet it would be unfair to say that all young people have turned away from it. Classics continue to be read, and contemporary writers are celebrated. Arundhati Roy’s works, for instance, are eagerly awaited, while authors like Vinod Shukla, this year’s Jnanpith awardee, are reaching wide audiences. Regional writers, too, are finding new life through translation. These signs remind us that while popular culture may reshape reading habits, it cannot erase the enduring relevance of high literature.

As a woman activist talking to another woman, a writer, scholar of psychology, I want to ask you a question that often troubles me. What is it that has caused such a rot in society that misogynist films like Kabir, Animal, The Kerala Story are drawing crowds, that there are often reports that a son is assaulting his mother, a father is exploiting his daughter, men are cutting their spouses to pieces and infants or deaf-mute girls are being subjected to sexual abuse and murder? What has gone wrong with our society? Why is there no adequate response? Are people getting desensitised? What can be done so that this doesn’t become normalised?

The rot in society stems from many factors. We have not been able to get rid of patriarchy and misogyny completely in the sub-continent, though there has been some progress. We still shy away from imparting sex education to the young.

The pressure of the population has resulted in large-scale unemployment. Idle youngsters who have not much to do are drawn to crime, and many eventually end up pursuing anti-social activities. The failure of our judicial system further compounds the problem and is perhaps the biggest contributing factor. Rape cases, for example, need to be fast-tracked and require special fast-track courts. In the present structure, most of the accused go free because the passage of time either destroys evidence against them or gives them the time and means to abscond. Punishment should be severe and quick. Justice delayed is justice denied.

I am not advocating capital punishment here, except in the rarest of rare cases, but for timely and proportionate sentencing and punishment. We can see that there are reports that in Saudi Arabia and the Emirates, no rape cases are reported. Women walking alone, even in the dead of night, are completely safe.

We need sensitisation of women through education for not stigmatising the victims, while protecting their sons; also, instilling in their sons and brothers a sense of dignity and respect for women.

Some time ago, I had the opportunity to write for the neo-literates of rural areas, teaching them about hygiene, nutrition and family values. The resource centres in rural areas have stopped working. I think that reviving that initiative can help in countering misogyny and inculcate other gender related values in rural society.

It is equally essential to teach girls ways of self-defence. And to give them the confidence and support to be able to confide in their parents and/or authorities, if they are the victims of such incidents.

I am sorry to say that the attitude of the present government is not sympathetic to women. People with political connections abuse women, and they are, in turn, protected. In certain cases, and with alarming frequency recently, a communal angle is quickly added. In some cases, raping a woman from the ‘other community’ seems not only acceptable, but is, in fact, lauded.

The biggest evil perhaps, is the rampant and systematic hate campaign. I feel very disheartened and dejected, but fight we must. And every effort, however small, matters.

Recently, I saw your book Bullah ki jana mai kaun published by Rekhta Publications. What was the Firogh-e-Urdu Adab award about?

Bullah ki Jaana main kaun was not published by Rekhta -- only a Hindi version was published by them. The Firogh-e-Urdu Adab award, presented at Doha, Qatar, is for general contribution to Urdu literature and, as such, acknowledges my entire body of work, rather than any specific publication.

What is your next project? Would you like to give a message to the young women and men of today?

My next project is the Urdu translation of Krishna Sobti’s autobiography Gujarat Pakistan se Gujarat Hindustan tak, and a collection of short stories titled Bargad, which is coming shortly.

My message to everyone, man or woman, young and old, is to preserve goodwill and to counter prejudice in peaceful ways.