a bond deeper and more enduring than many marriages…

- Independent Ink

- Jan 26

- 5 min read

Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood: Who would want to marry a person who doesn’t really want to marry you, for whatever ludicrous reason?

By Beena Vijayalakshmy in Toronto

The moment when, after many years of hard work and a long voyageyou stand in the centre of your room, house, half-acre, square mile, island, country,

knowing at last how you got there, and say, I own this,is the same moment the trees unloose their soft arms from around you…

No, they whisper. You own nothing. You were a visitor…It was always the other way round.

— The Moment

Time and again, this poem by novelist and poet Margaret Atwood has come to my rescue, quietly reminding me to remain humble and to accept that nothing in life is truly permanent. My favourite poem of hers is Variation on the Word Sleep. I think it is among her most intimate and tender creations. A reminder of just how magnificently Atwood writes.

I would like to be the air that inhabits you for a moment only.I would like to be that unnoticed and that necessary.

I have long been captivated by Atwood, the poet, just as much as by Atwood, the novelist. At 86, she offers us Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts, a deeply moving reflection that spans wars, cultural upheavals, and personal transformations. She remains with us, telling the story of a life lived openly and attentively in history’s gaze.”

She came into my life quietly. A friend had invited me over for a playdate with my son, and by sheer coincidence, I found myself at a book sale at her son’s school. Of all the books on offer, the blurb of Life Before Man resonated with me. I was unaware at the time that I was holding the work of one of the defining voices of Canadian literature. That book found me before I knew I was looking for it.

Life Before Man is a novel of entangled relationships, desire, and disappointment. Of lives that resist tidy resolution.

Its contours were shaped, in part, by her own experiences, especially her enduring relationship with Graeme Gibson. It was the first of many Atwood books I would read.

It was the first of many Atwood books I would read. From there I sought out her novels, her poetry, her essays, each work offering new insights into power, memory, and the art of survival. It was not until I encountered her memoir this year that I realized how deeply her own life events had informed her literature.

The honesty is striking.

She writes with the kind of candour that makes you feel she has set down words without worrying who might read them. “The only way you can write the truth is to assume that what you set down will never be read.”

Margaret Atwood was born in Ottawa in 1939, raised partly in northern Quebec and Toronto, with summers spent in remote wilderness alongside her scientist parents. Those years of solitude and curiosity sharpened the imagination that would echo through her fiction.

Across more than six decades, she has built a body of work that refuses boundaries: novels, poetry, essays, short stories, children’s books, even graphic novels. Her influence has been global.

The Handmaid’s Tale became a cultural touchstone, adapted into an Emmy‑winning television series and embraced as a symbol of resistance against authoritarianism and patriarchal control. Recognition followed.

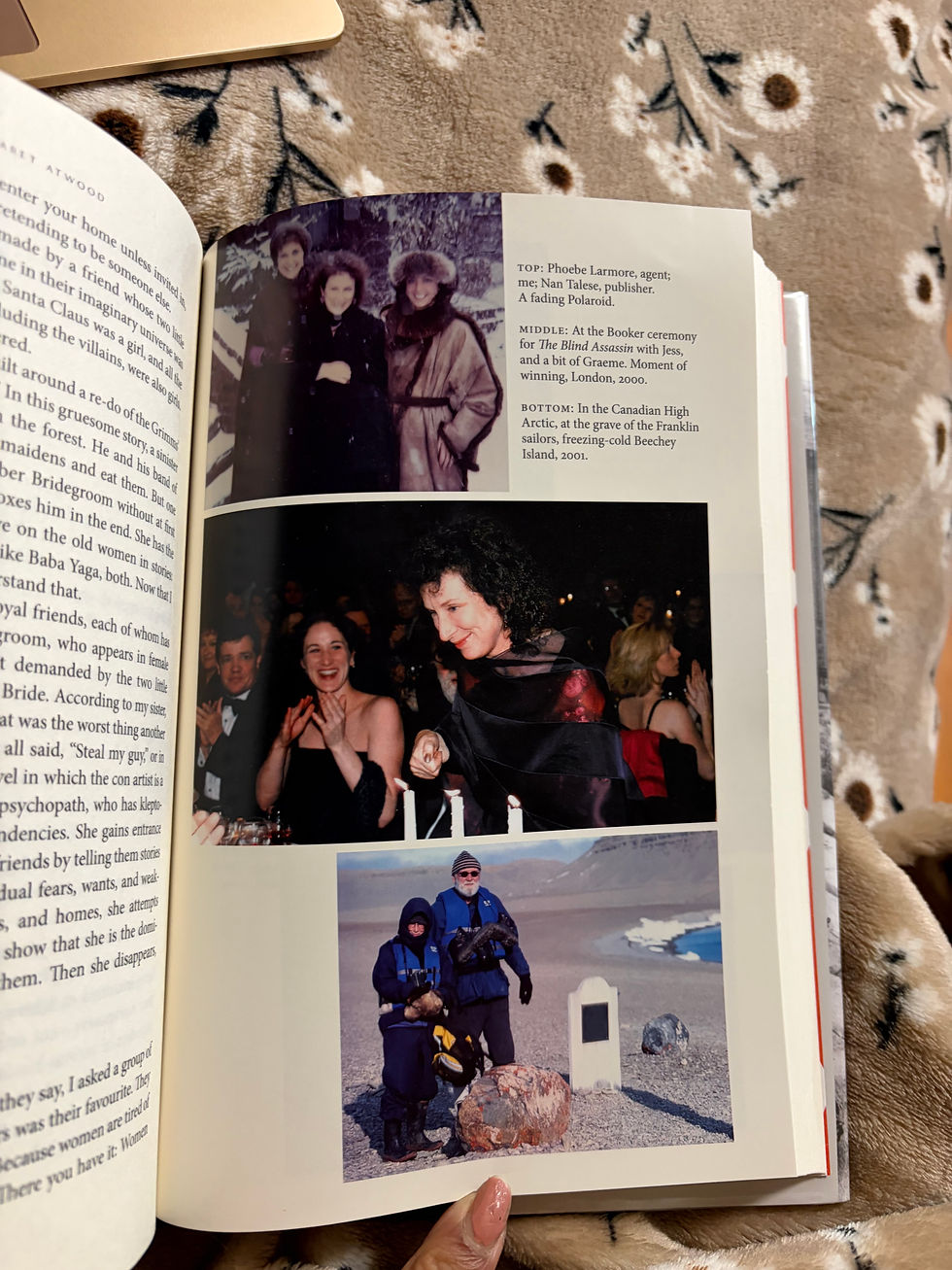

Booker Prize, Governor General’s Awards, and a host of international honours, each a testament to how her voice has carried across cultures and generations, speaking to the enduring anxieties of our time. Atwood’s life and work trace a chronology of imagination that endures, adapts, and retains its urgency in the face of history’s constant flux.

While she recounts her life in meticulous detail, it is her relationship with Graeme Gibson that I found most compelling. She never took his name, never became ‘Mrs Gibson,’ yet, together, they forged a bond deeper and more enduring than many marriages — a partnership built on trust, respect, and quiet devotion.

Excerpt from Book of Lives: A Memoir of Sorts by Margaret Atwood.

However, he has noticed the creeping chill and has divined the cause. He has now attempted to soothe my injured amour propre by proposing to me—but who would want to marry a person who doesn’t really want to marry you, for whatever ludicrous reason? He has also presented me with one of his most cherished possessions—a small, ancient Inuit carving of a white weasel, complete with black inset whiskers. He says it’s an Engagement Weasel instead of an engagement ring, though he eventually got me one of those too.

The Engagement Weasel is very touching, but not something that can be easily explained in, for instance, newspaper interviews. (“An engagement what?”) It seems I must impersonate a rigid anti-marriage ideologist, which is contrary to the truth of the matter.

I dislike being penned up in this ridiculous cul-de-sac. It’s eating away at me. Should there be a Revelation Scene, in which I whip off my smiley mask to reveal the enraged harpy within? Should I walk out? With a young baby? Not so easy; also, why should I mess up this child’s life by removing her from a father who adores her, as well as me? And if I do walk out, what a high-schoolish reason for doing so?

I suppose that what I really resent is my loss of—as they say—agency. Also, the duped feeling that I bought a gold brick on spec that turned out not to be gold, though that purchase came from my own assumptions. Did the two of us ever truly discuss the future, apart from Graeme’s conviction that it would be permanent and wonderful?

Reading this now, with the benefit of hindsight, the Engagement Weasel now feels more like a quiet emblem of the life she and Graeme Gibson went on to build. They never married, despite the expectations of the time, despite the social pressure to give their partnership a sanctioned form.

Yet, theirs was a deeply wholesome relationship, grounded in mutual regard.

Gibson made space for her work; he did not intrude upon it. He cooked, he waited, he noticed. She trusted him with her life, her child, and her becoming.

In resisting the form, they preserved the substance, and in doing so, they modeled a way of loving that was quietly radical for its time. She writes of his decline without sentimentality, with quiet endurance, and comes across as deeply human and unsparing when she writes about Shirley, Gibson’s ex-wife.

In the end, Book of Lives reveals the texture of a life lived with attention. It reminds us that stories grow out of the smallest things, that memory itself is a kind of art, and that the line between life and literature is porous.

Reading it, I felt again the quiet thrill of that gymnasium book sale years ago, the sense that a book can find you when you need it most, and that some voices stay with you long after you have closed the final page.

Beena Vijayalakshmy is a writer and translator with roots in Kerala, now based in Toronto. An avid reader and lover of literature, she has edited two poetry anthologies -- Bards of a Feather, Volumes 1 and 2, and curates a literary page on her social-media handle that showcases the work of poets, writers, and artists from around the world for a growing global audience. By profession a management consultant, she balances her corporate career with a lifelong commitment to literature and the arts. In keeping with her philosophy of lifelong learning, she is currently pursuing a degree in management at the Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto. By her own admission, she prefers to remain on the sidelines in the quiet spaces between prints.

Photos courtesy Beena Vijayalakshmy.